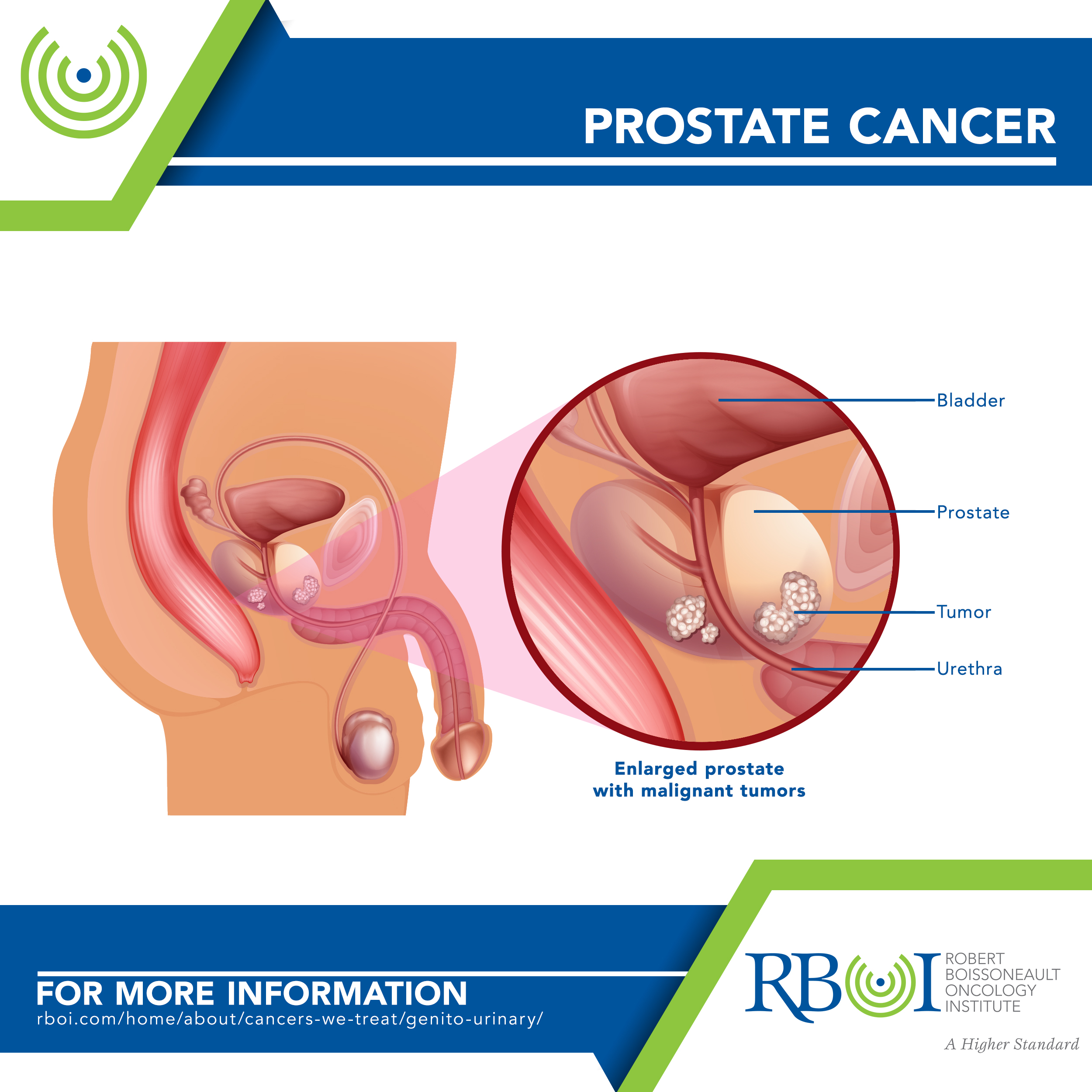

Prostate Cancer

Prostate cancer is the most common cancer among men in the United States. Some prostate cancers grow very slowly and may not cause symptoms or problems for years or ever. Even advanced prostate cancer can be managed with good health and quality of life for a long time. But other prostate cancers are more aggressive. Monitoring for tumor growth is an important part of managing this disease. Screening is done with a blood test that measures prostate-specific antigen (PSA).

Click here to learn more about RBOI’s radiation treatment options

Click here to watch a walk-through of what is involved in radiation treatment at RBOI

More extensive information about prostate and other cancers may be found at these sites:

American Cancer Society: Cancer.org

American Society of Clinical Oncology: Cancer.net

National Cancer Institute: Cancer.gov